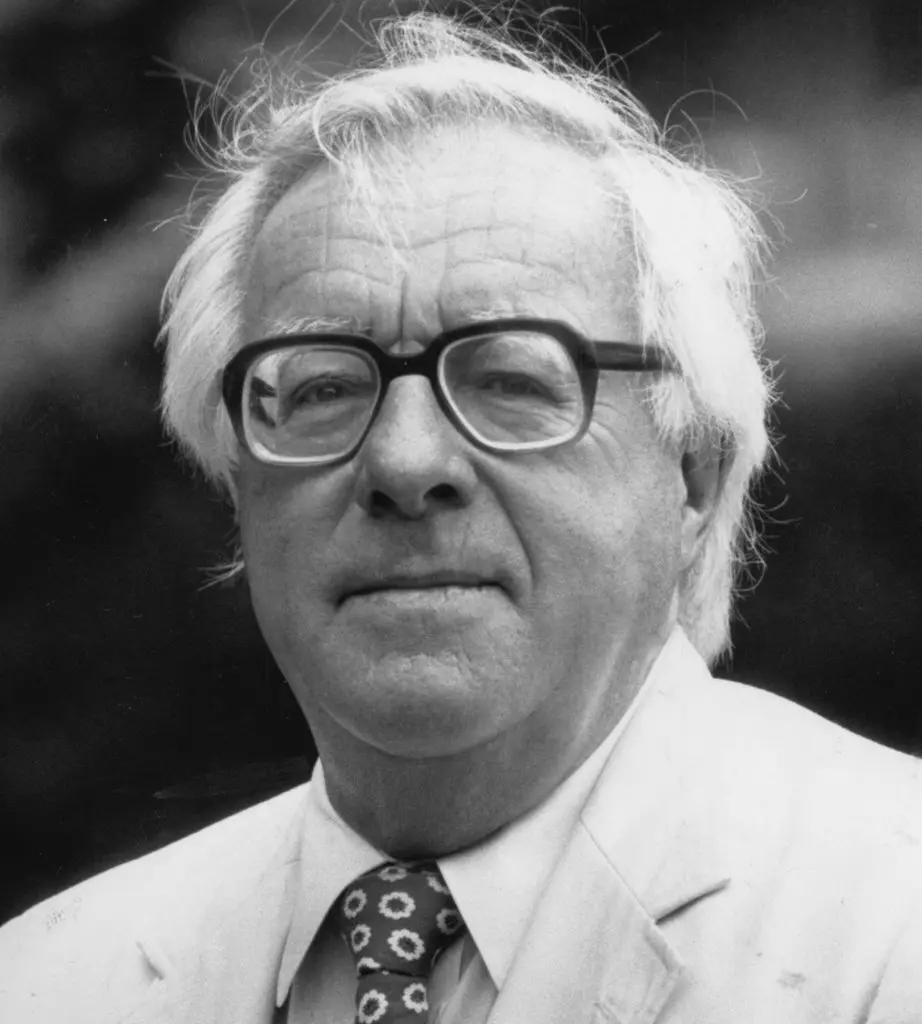

If perspicacity and foresightedness are criteria for the greatness of a narrative then ‘Fahrenheit 451‘ by Ray Bradbury (Ray Bradbury – Books, Short Stories & Quotes) stands tall.

First published in 1953 the author imagines a dystopian future in which a totalitarian state has prohibited books and reading. The populace is driven into conformity by means of giant floor-to-ceiling entertainment walls which play a continuous stream of infantilising mass media content.

‘Firemen’ have become licensed arsonists who hunt down readers, burning their books and houses. Free thought and dissent are ruthlessly expunged. One such fireman, Guy Montag, becomes disillusioned having had a short series of conversations with a young neighbour who is uncommonly liberated in her thinking. He has also noticed that his wife Mildred is in a constant stupor, consuming quantities of sleeping pills. The happiness of the population is clearly at variance with the constant propaganda pumped out by the state.

Montag risks death by acquiring and beginning to read books, all the while under the close scrutiny of the chief at the fire station, Captain Beatty, a loyal functionary. Beatty had previously been a reader but renounced the habit as being seditious and failing to achieve happiness.

Beatty himself explains the history of the ‘fire service’ to Montag – ‘Once, books appealed to a few people, here, there, everywhere. They could afford to be different. The world was roomy. But then the world got full of eyes and elbows and mouths. Double, triple, quadruple population. Films, and radios, magazines, books levelled down to a sort of paste pudding norm, do you follow me?’

Bradbury cannot have known, in 1953, about the hundreds of cable and satellite channels that would be fed into people’s homes by 2024. Nor about the smartphone and social media which have done so much to shorten attention spans. Nor about about the enormous bewitchment of computer gaming across the world. Nor about immersive headsets and virtual reality. His chilling vision in which a society has forgotten freedom of thought is highly topical for our times. The thought police are amongst us in many guises. Dictatorships proudly exert their influence on the world stage of 2024.

Throughout the book Bradbury’s descriptive prose is strikingly good. For example, on page 65 (Harper Voyager edition, 2008) we are given a description of Mildred – ‘… he saw her without opening his eyes, her hair burnt by chemicals to a brittle straw, her eyes with a kind of cataract unseen but suspect behind the pupils, the body as thin as a praying mantis from dieting, and her flesh like white bacon’.

Again, on page 154, the moment in which Montag burns Beatty alive with a flame thrower is described thus – ‘And then there was a shrieking blaze, a jumping, sprawling, gibbering mannikin, no longer human or known, all writhing flame on the lawn as Montag shot one continuous pulse of liquid fire on him. There was a hiss like a great mouthful of spittle banging a red hot stove, a bubbling and frothing as if salt had been pored over a monstrous black snail to cause a terrible liquefaction and a boiling over of yellow foam’.

The book is not a cry of utter despair. There is hope that a few literate souls might preserve the torch of free thought and resistance. Poetry plays a part here, and Montag is depicted as reading aloud Matthew Arnold’s poem ‘Dover Beach‘ (first published 1867, Dover Beach | The Poetry Foundation) to Mildred’s friends. Although also a despairing vision of humanity which has lost faith, it clings to hope in the line ‘Ah, love, let us be true To one another!’

Although published over 70 years ago now, this book remains relevant to our times and is well worth a read.

First published 1953

227 pages in Harper Voyager paperback

ISBN -13 978 0 00 654606 1