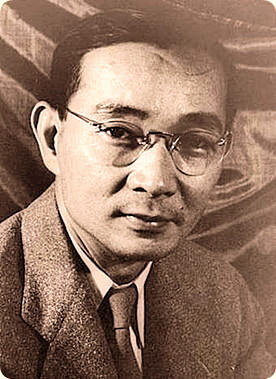

China has achieved a staggering transformation in the last 30 years, and now stands on the threshold of becoming the world’s largest economy. It is flexing its military muscle in the South China Sea, whilst at the same time building transport links to the West which will allow rapid export for its vast manufacturing output. Xi Jin Ping has been elevated to President for life in March 2018. The nation remains a one party state under the Communist Party, but it is a fantasy to think anything like communism has been achieved in the country. Huge disparites in wealth and power have opened up under its state sponsored turbo capitalism (https://www.ft.com/content/3c521faa-baa6-11e5-a7cc-280dfe875e28). In view of the global importance of China in the modern world it is unsurprising that there is an industry of English language material attempting to interpret its historic and modern significance. One publication that has lasted, and remains a pleasure to read, is My County and My People by Lin Yutang (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lin_Yutang).

Published in 1935, this was the first major work by a Chinese author to introduce China and her culture to the West. Lin was born in China, but was educated in America and Europe. He was a key figure in the New Culture Movement of the 1920s, but after 1935 spent most of his life in the America. He was the compiler of a Chinese – English dictionary which is still one of the most widely used today, and the inventor of the first Chinese language typewriter – a kind of Renaissance Man. He was ideally suited, then, as an interpreter of his own culture.

Lin’s book covers subjects as diverse as the role of women, the Chinese mind, the importance of calligraphy as a way to understand Chinese culture; he gives potted histories of Chinese literature and painting; he teases out patterns of circularity and repetition within and across the various Dynasties; he discusses the importance for the Chinese of their houses and gardens, tea culture, Conficianism and The Golden Mean.

Of the Confucian ideal of the gentleman ruler (junzi 君子), ruling by example through correct morality, Lin notes: ‘it is a queer irony of fate that the good old school teacher Confucius should ever be called a political thinker, and that his moral molly-coddle stuff should ever be honored with the name of a political theory’. He notes the difference between form and substance, or appearance and reality, one of the key tensions in Chinese life, between a political theory that emphasizes virtue and morality, and yet which gave rise to the most consistently corrupt and incompetent governments the world has ever seen.

Of the five relationships as defined by Confucius – ruler to ruled, father to son, husband to wife, elder brother to younger brother, friend to friend, Lin notes the omission of the relationship between stranger and stranger, and calls this a great and catastrophic omission, and one that partly accounts for the lack of a civic consciousness in Chinese life, the complete indifference to others outside one’s own family circle. He believes it accounts for lack of manners, the lack of what he calls a Samaritan spirit, and the all pervasive presence of nepotism and venality in public life.

Mentality is determined by language, and of the Chinese mind Lin notes the absence of logic as Westerners understand it. He describes how, instead, there is Chinese ‘common sense’, and also a kind of Taoist philosophy which holds truth to be something above words. We can consider the opening lines of the Tao Te Ching: ‘The Way that can be spoken of/ Is not the constant Way/The name that can be named/Is not the constant name’. Lin also guides us into Chinese literature. He presents poems, excerpts from the histories, essayists and novelists from all dynasties.

My County and My People is inevitably dated in some respects. It contains many references to race, the purity of ‘Han blood’ and the necessity for its reinvigoration. ‘Race’ and ‘blood’ are common tropes of the sociology of the 1930s, and Lin spent much of the 1930s in Germany, where notions of racial purity abounded. He is also dated in his discussion of the role and nature of women in Chinese life. His solution for China’s ills is to shoot the officials, and he ends the book with an image of the Great Executioner cleansing out the stables of government. We now know that Chiang Kai Shek, the Japanese, Mao, and Deng Xiao Ping all tried that in one form or another. Today’s leaders show equal enthusiasm for elimination of undesirables. Yet the fundamental problems which are deeply rooted in Chinese culture still persist.

Nevertheless, My Country and My People has an energy and idiosyncrasy of vision which has lasted. There are pithy and memorable epigrams which interpret Chinese culture perfectly well today. Check if this classic of Chinese cultural anthropolgy is in stock at your local library by consulting the online catalogue at https://www.sllclibrary.co.uk/cgi-bin/spydus.exe/MSGTRN/OPAC/BSEARCH

Read this alongside Age of Ambition (2014) by Evan Osnos (a former New Yorker correspondent), for a picture of hyper-dynamic modern China. (https://www.amazon.co.uk/Age-Ambition-Chasing-Fortune-Truth/dp/0374280746/ref=tmm_hrd_swatch_0?_encoding=UTF8&qid=1521989968&sr=1-1). Osnos has an engaging writing style, and presents an appealing set of characters. They represent the spectrum of what a citizen of modern China faces: overnight success, optimism, insecurity, fear, and hope. There are figures like artist and activist Ai Weiwei, whom he befriended in Beijing, and former World Bank chief economist Justin Lin, who defected to mainland China from Taiwan in 1979, as well a striving Chinese English student named Michael Zhang. Osnos offers the full historical context of events that inspired characters living in what he calls China’s ‘Gilded Age’.

370 pages in Important Books

First published 1935

ISBN 978-1773231181

Lin Yutang